After the commotion of the announcements, when the claps and screams were already fading and people started to get up to leave the stands, I said to Nate: “I’m going to try to talk to someone backstage, OK? Maybe I will find a good story there”, and quickly went down the stairs. It was easy to get back stage, where girls were being hugged, mothers carried sashes, clothes and flowers and the atmosphere was pure joy. Little Miss Cherokee 2016 had just been crowned and the event was closed for the night. There would only be more coronations, dance, music and smiles tomorrow, another day of the Annual Cherokee Indian Fair, which we happened to enjoy during our time on the Cherokee Indian Reservation, in North Carolina.

In fact, it wasn’t the Cherokees who exclusively brought us to that part of North Carolina, even if indigenous things are one of the motivations on our trip, as anything related to native cultures make Nate’s eyes shine – he graduated with honors (pride!) in History with an honor’s thesis on Navajo peyotism. Deep in our hearts, the reason for us to drift off the coast and into the state was the mountains of western North Carolina, the Great Smoky Mountains, long on the list of places he has always wanted to see.

Depois da comoção dos anúncios, quando as palmas e gritos já esmoreciam e as pessoas começavas a se levantar pra deixar a arquibancada, falei pro Nate: “vou ali tentar conversar com alguém, tá? Vai que rende pra alguma matéria?”, e desci as escadas rapidamente. Foi fácil chegar atrás do palco, onde várias meninas eram abraçadas, algumas mães carregavam faixas, roupas e flores e o ambiente era de pura alegria. A Miss Mirim Cherokee 2016 – ou seria Miss Infantil? – acabava de ser coroada e o evento estava encerrado pela noite. Mais coroação, dança, música e sorrisos, só amanhã, em mais um dia do Festival Anual Cherokee, que por acaso tivemos a sorte de desfrutar em nossa passagem pela Reserva Indígena Cherokee, na Carolina do Norte.

Na verdade, chegamos ali não exclusivamente pelos Cherokees, apesar do Nate gostar muito de tudo que se refere a cultura de nativos – ele se formou com honras (orgulho!) na faculdade de História com um trabalho final sobre o uso do peiote pelos Navajos – , e esse até ser um dos fios condutores da nossa viagem. No fundo, o motivo pra desviarmos da costa e adentrarmos o estado foram as montanhas do oeste da Carolina do Norte, as Great Smoky Mountains, há tempos na lista de lugares que ele queria conhecer.

The Great Smoky Mountains, part in North Carolina, part in Tennessee and named after the ever-present mist in the morning, are the most visited national park in the United States. One of the two visitor centers, Oconaluftee (cool sound!), takes its name from the river that runs through the park and the Cherokee Reservation, right next door.

The plan was to camp in Cherokee to get to know the city and do some trails in the national park. After three days, we would head to South Carolina. But everything changed with the arrival of Hurricane Matthew in the United States. After devastating Haiti (it always gets hit!), and leaving destruction in the Dominican Republic and Cuba, the alert from Florida to North Carolina was at a maximum. “Do not come, stay there a few more days”, Aunt Jane, our next hostess, warned us. It didn’t make us upset, actually. We met some people who had left South Carolina in search of shelter in the mountains of Cherokee while the hurricane was around. On our first day there, the manager at the campground suggested that we go to the parade in town. And that’s how we found out that Cherokee was going to party the whole week with the Annual Cherokee Fair.

How lucky! Our Cherokee immersion wouldn’t be limited to visiting the museum. During the week, between trails and bike rides, we made the most of the festival’s program. We saw Misses being crowned, songs and ceremonies being performed, Stickball being played, we talked to real Cherokees and spent a few hours in the museum. I knew nothing about their way of life. Totally clueless, for me Cherokee was not much more than the name of a car. I learned that, in fact, they are Americans like any other, trying to keep their culture alive day to day, with their own language, food, and customs. Like any other immigrant, with the detail that they were here before everyone else.

As Great Smoky Mountains, assim batizadas por conta da neblina sempre presente pela manhã (smoky = esfumaçado), são o parque nacional mais visitado dos Estados Unidos. O parque abrange partes da Carolina do Norte e do Tennessee. Um dos dois centros de visitantes, Oconaluftee (som legal!), leva esse nome por conta do rio que percorre o parque e a Reserva Cherokee, bem ali ao lado.

O plano era acampar em Cherokee pra aproveitar e conhecer a cidade e fazer umas trilhas no parque nacional. Depois de três dias, seguiríamos para a Carolina do Sul. Mas tudo mudou com a chegada do furacão Matthew aos Estados Unidos. Depois de arrasar o Haiti (sempre ele!), e deixar destruição na República Dominicana e Cuba, o alerta da Flórida até a Carolina do Sul era máximo. “Não venham! Fiquem aí mais uns dias”, nos alertou Tia Jane, nossa próxima anfitriã. Nem achamos ruim, na verdade. Chegamos até a conversar com um pessoal que havia justamente saído da Carolina do Sul em busca de abrigo nas montanhas de Cherokee enquanto o furacão não desse trégua. No nosso primeiro dia por ali, o moço do camping sugeriu que a gente fosse ver o desfile que passaria ali na entrada. E foi assim que descobrimos que naquela semana a cidade estaria em festa por conta do Festival Anual dos Cherokees.

Que sorte! Não só de ida ao museu seria nossa imersão cherokeeana. Durante a semana, entre trilhas e pedaladas, aproveitamos ao máximo a programação do festival. Vimos misses serem coroadas, canções e cerimônias serem realizadas, o jogo de stickball (super violento!), conversamos com Cherokees de verdade e passamos algumas horas no museu. Não tinha ideia de como era o modo de vida ali. Alienada, pra mim Cherokee significava, até então, bem pouco além do nome de um carro. E vi que, na verdade, são americanos como outros quaisquer, tentando manter viva sua cultura no dia a dia, com o idioma, as comidas, os costumes. Como imigrantes que estavam aqui antes de todo mundo.

The Cherokees are the most populous indigenous group in the United States. To be considered Cherokee, ancestry doesn’t need to come from both parents. Today, there are about 260,000 people who call themselves Cherokee, living in different parts of the world. In North Carolina, one of the states where they were originally established, there are about 12,500 Cherokees. In Oklahoma, where the Cherokee Nation is, there are 120,000.

Like all indigenous peoples who had contact with Europeans in the 16th century, the Cherokees went through hell and back. After attempts to remove them from their lands, obviously frustrated, the US government decided to use force. The removal law, signed by President Andrew Jackson, gave three years, from 1836 to 1839, for the Cherokees to leave North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Georgia, and Alabama to go west, beyond the Mississippi River, toward the so-called Indian Territory, in the state of Oklahoma. The further, the better. More than 4,000 Cherokees died along the way, today it is known as the “Trail of Tears”.

Os Cherokees são o grupo indígena mais populoso dos Estados Unidos. Pra ser considerado Cherokee, a ascendência não precisa ser de pai e mãe. Hoje, são cerca de 260 mil pessoas que se auto-denominam Cherokee vivendo em diferentes partes do mundo. Na Carolina do Norte, um dos estados onde eles estavam originalmente estabelecidos, são cerca de 12.500 pessoas. Em Oklahoma, onde está a Nação Cherokee, são quase dez vezes mais, 120 mil.

Como todos os povos indígenas que tiveram contato com os europeus no século 16, os Cherokees comeram o pão que o diabo amassou. Depois de tentativas de acordo obviamente frustradas para retirá-los de suas terras, o jeito foi usar a força. A lei de remoção, assinada pelo presidente Andrew Jackson, dava um prazo de três anos, de 1836 a 1839, pros indígenas saírem da Carolina do Norte, do Sul, Tennessee, Texas, Georgia e Alabama em direção a oeste, pra lá do Rio Mississipi, em direção ao assim batizado Território Indígena, no estado de Oklahoma. Quanto mais longe, melhor. Acredita-se que mais de 4 mil Cherokees tenham morrido no trajeto, hoje conhecido como “Caminho das Lágrimas”.

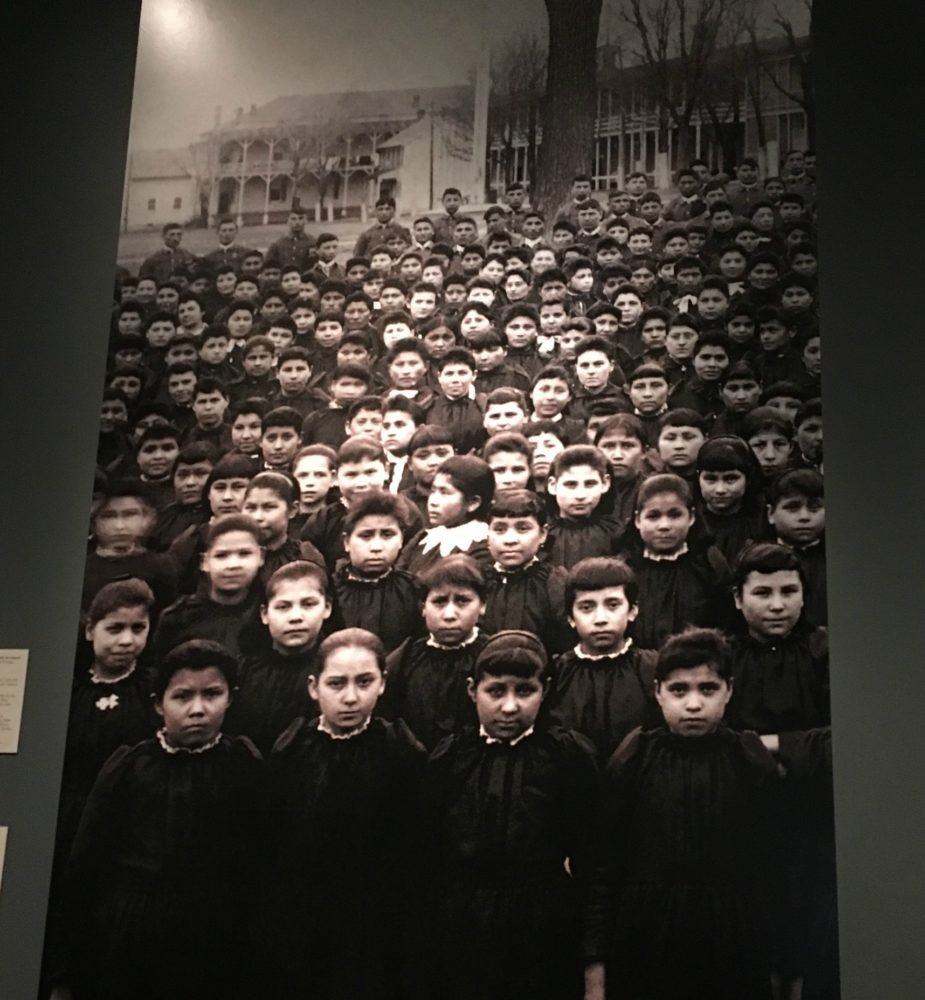

If it was a little disgraceful, it would end there. But no, there is more. In addition to forced removal, Cherokee children (along with countless other tribes) were also sent to boarding schools. They were given a Christian name, haircut and European clothes, could not use their mother tongue and were many months away from their families.

In an exhibit we visited in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, a few days earlier, one of the posters said: “In the 19th century, cultural assimilation and removal – voluntary or forced – were cornerstones of US Indian policy. In 1860, the US Bureau of Indian Affairs established boarding schools to assimilate Native children into mainstream American life. The Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania prepared Native students for industrial labor and “civilized” life by teaching them English and history, along with domestic and trade skills. Open from 1879 t to 1918, the Carlisle enrolled over 12,000 students. JN Choate advertized the benefits of the school and its civilizing process by producing “before and after” photographs of students in their Native dress and in their school uniforms, highlighting their transformation. ”

Se desgraça pouca fosse bobagem, acabava aí. Mas não, tem mais. Além da remoção forçada, teve também as escolas internas, pra onde as crianças eram obrigatoriamente enviadas. Ganhavam nome, corte de cabelo e roupas europeias, não podiam usar o idioma materno e ficavam meses longe da família.

Numa exposição que visitamos na Filadélfia, Pensilvânia, uns dias antes, li em um dos cartazes dizia: “No século 19, assimilação cultural e remoções – voluntárias ou forçadas – foram marcos da política indigenista nos Estados Unidos. Em 1869, o US Bureau of Indian Affairs estabeleceu escolas internas para assimilar crianças nativas nos moldes do modo de vida americano. A Carlisle Indian Industrial School, em Carlisle, Pensilvânia, preparava os estudantes nativos para o trabalho industrial e a vida “civilizada” ensinando-lhes inglês e história, bem como habilidades domésticas e de comércio. Em funcionamento de 1879 a 1918, a Carlisle teve mais de 12 mil alunos. J.N. Choate divulgava os benefícios do processo civilizatório produzindo fotos de “antes” e “depois” dos alunos em seus trajes típicos e em seus uniformes escolares, dando destaque à sua transformação”.

This policy was traumatic for native communities throughout the United States, Canada and Australia. And the consequences are still felt today, a century after this forced practice of boarding schools has been abolished – some schools still seem to be functioning.

But not only of sad facts is made the museum. I learned better about Sequoyah, the indigenous who in the 1820s created the writing system for the Cherokee, based on syllables. The alphabet was quickly adopted and the Cherokees came to create a newspaper and publish their constitution. But my favorite part would be women’s responsibility. I learned that, traditionally, Cherokee women always enjoyed the same rights as men, including sexual freedom and the choice of the spouse.

In Cherokee, we saw lots of overweight people. Even though it’s unfortunately something common in the United States, it’s always kind of scary getting to a place and realizing that obese people are the rule, not the exception. At the festival, I was super curious to try typical Cherokee food. Again shocked, I thought it would be healthy dishes, made by hand by people living off the land. How naive. The lines were all for the stands selling fried bread (like fried dough or funnel cake), one of the only things available. It was served with chili, as a version of Mexican tacos, or as a dessert, with bananas, strawberries and sugar on top.

Essa política foi traumática para comunidades nativas em todos os Estados Unidos, Canadá e Austrália. E as consequências são sentidas ainda hoje, um século depois dessa prática forçada dos internatos ter sido abolida – ainda assim, algumas escolas parecem ainda estar em funcionamento.

Mas nem só de tristezas é feito o museu. Lá conheci melhor a história do Sequoyah, o indígena que nos anos 1820 criou o sistema de escrita para os Cherokee, baseado em sílabas. O alfabeto foi rapidamente adotado e os Cherokees chegaram a criar um jornal e publicar sua constituição. Mas a parte favorita ficou por conta das mulheres. Aprendi que, tradicionalmente, as mulheres Cherokee sempre gozaram dos mesmos direitos dos homens, inclusive no que tange à liberdade sexual e escolha do cônjuge.

Em Cherokee, vimos muitas pessoas muito gordas. Mesmo sendo algo até comum nos Estados Unidos, é sempre meio assustador chegar a um lugar e se dar conta que obesos ali são regra, não exceção. No festival, estava super curiosa para experimentar comida típica Cherokee. De novo alienada, achei que seriam pratos saudáveis, de quem vive da terra. Mas não. As filas eram todas nas barracas de fried bread, praticamente a única iguaria disponível, uma massa frita com outros ingredientes por cima. Podia ser carne moída com molho de tomate, alface e queijo ralado, meio que uma versão dos tacos mexicanos, ou na versão sobremesa, com banana, morango e açúcar por cima.

Anyway, it was very interesting to be there during the festival, when cultural manifestations abound. I was surprised to follow the Miss contest and see different criteria from what (I imagined) govern Miss’s contests in the non-native world. There is, for example, no weight or measures restrictions. Most of the candidates were pretty chubby. Instead of modeling in a swimsuit (this is a part of others, right?), it’s important here to show a beautiful, traditional Cherokee costume. Shoes are all deer hide, no high heels (how wonderful!), with embroidered beads. Baskets, feather cloaks, belts, every detail matters. It’s also important to do well in the cultural presentation. It can be singing a song in Cherokee, telling a story, performing a dance. The Cherokee language, actually, is being offered again in public schools in the city.

De qualquer jeito, foi muito interessante estar ali durante o festival, quando as manifestações culturais abundam. Fiquei surpresa ao acompanhar o concurso de Miss e ver critérios diferentes dos que (eu imagino) pautam os concursos de Miss no mundo não nativo. Não há, por exemplo, restrição de peso ou medidas. A maioria das candidatas era bastante gordinha. Ao invés de desfile com maiô (existe isso nos outros, certo?), aqui se dá extrema importância ao traje típico. Sapatos são todos de pele de veado, nada de salto (que maravilha!), com miçangas bordadas. Cesta, capa de penas, cinto, cada detalhe importa. No concurso, é importante também se sair bem na apresentação cultural. Pode ser cantando uma canção em Cherokee, contando uma lenda, apresentando uma dança. O ensino do idioma Cherokee, aliás, voltou a ser oferecido nas escolas públicas da cidade.

I just found it strange that on the jury, from what I could see from afar, there was no Cherokee. It is true that, to be considered Cherokee, one has to have 1/16 Cherokee descent, or a grandparent, so perhaps the three blond female jurors and the only male juror, an Afro-American gentleman, were all Cherokees. Or maybe it’s important to have no blood connections to avoid judging on behalf a family member. In 2015, for example, Miss Cherokee was crowned, and a few days later, when the adrenaline of having the crown on her head had not even gone down, she received a call saying that there had been a mistake in counting the points and I am sorry, but you are not Miss Cherokee 2015. Can you imagine? Some say it might have been political influence from some chief of some group that wasn’t happy with the results, but who knows? The young lady did not settle and this year she decided to participate again, an arduous process that demands months of study and preparation.

And it was her that I met backstage when I came downstairs breathless. But this story, and how it felt to hug a Miss for the first time in my life, will be told at some point in the near future.

Só achei estranho que, no júri, pelo que pude observar de longe, não havia nenhum Cherokee. É verdade que, como para ser considerado Cherokee, é permitido até 1/16 de ascendência, talvez as três juradas loiras e o único jurado homem, um senhor afro-descendente, fossem mesmo Cherokee. Ou quem sabe seja importante não ter nenhuma ligação sanguínea para não cometer nenhuma injustiça na hora do julgamento. Em 2015, por exemplo, a Miss foi coroada e, uns poucos dias depois, quando a adrenalina de ter a coroa na cabeça ainda nem tinha baixado, recebeu uma ligação dizendo que houvera um engano na contagem dos pontos e que não, ela não havia ganhado. A Miss era outra. Cara, imagina! Alguns dizem que pode ter dedo político aí, alguém relacionado ao chefe de alguma tribo não gostou do resultado. De um jeito ou de outro, a moça não se conformou e esse ano resolveu participar de novo, um processo árduo que demanda meses de estudo e preparação.

E foi ela que eu encontrei ali atrás do palco quando desci esbaforida atrás de uma pauta. Mas essa história, e como foi a emoção de abraçar pela primeira vez na vida uma Miss, fica prum outro texto.

Leave A Comment